Yaakov Taubes

Review of Yehuda Meir Keilson, Kisvei HaRambam Volume 2: Conduct and Character The Writings of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon – The Rambam – Translated, Annotated and Elucidated (ArtScroll, 2024)

In late 2019, the hosts of Unorthodox, a popular (now defunct) podcast produced by Tablet Magazine, released The Newish Jewish Encyclopedia: From Abraham to Zabar’s and Everything in Between, an entertaining and somewhat whimsical introduction to various facets of modern Jewish life and culture, written in the form of alphabetically organized entries. Under “ArtScroll,” we find the following:

One of the largest and most prominent Jewish publishers of traditional books in the United States, founded by two Orthodox rabbis in Brooklyn in 1976. Known especially for the ArtScroll Siddur, a traditional, Orthodox Jewish prayer book used by many congregations over the past forty years, the staff has produced the entire Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds in English translation, as well as translations of the medieval biblical commentary of Rashi and Maimonides, plus other canonical texts of Jewish literature, including Susie Fishbein’s Kosher by Design Cookbook series.[1]

This is a perfectly reasonable and in-style description of the impact of the publishing house, with a note about their major accomplishments.[2] There is, however, an error: Maimonides did not write a biblical commentary, at least in the classic sense, and certainly not one that would be categorized with that of Rashi.[3] Even if we extend the parameters of the definition of “commentary” to mean the work of any medieval writer, the fact remains that when this entry appeared in print, ArtScroll had yet to translate any of the writings of Maimonides in a systematic fashion.

It is possible that this is a typo, and should rather read Nahmanides, i.e., R. Moses b. Nahman/Ramban, a translation of whose incredibly popular and influential Torah commentary ArtScroll indeed published in 2004.[4] But it is also possible that it was written under a logical, if false, assumption. After all, Maimonides is arguably the most well-known post-biblical Jewish figure – surely his wide corpus of writing must have been touched by ArtScroll![5]

As recently documented and displayed at a special exhibit at the Yeshiva University Museum dedicated to his writings, Maimonides’ name and ideas have long been in the public mind, associated with schools, hospitals, and more.[6] Moreover, his philosophy was referenced by non-Jewish philosophers already in the medieval period, when some of his work was translated into Latin, among other languages, and even today, his teachings are cited far outside the confines of the Jewish world. Now, ArtScroll of course publishes primarily for religious Jews, but Rambam’s stature is even greater there. The standard page of the Talmud includes citations to where the Rambam codified each given passage in his Mishneh Torah, one of the most important codifications of halakhah, and his commentary on the Mishnah is printed in the back of many editions of the Talmud and continues to be widely studied. His Sefer Ha-Mitzvot transformed the genre of mitzvah enumeration, while his Moreh Nevukhim is the most influential Jewish philosophical work of all time.

Indeed, one can find references to the Rambam throughout ArtScroll’s annotation of the Talmud, as well as in others works. Additionally, in late 2019, ArtScroll published an Introduction to the Talmud volume, which included a translation of both Maimonides’ introduction to Mishneh Torah and the introduction to his Commentary on the Mishnah. While this was certainly significant, there had yet to be a work devoted to Maimonides alone.

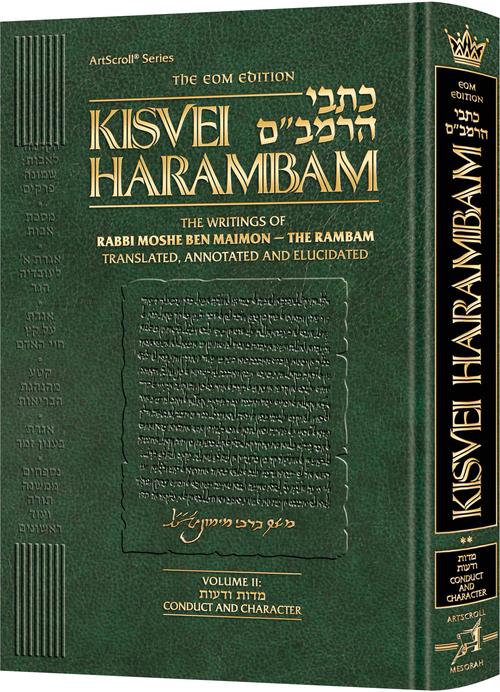

This all changed with ArtScroll’s publication of two volumes of Kisvei HaRambam, (in 2023 and 2024 respectively). The first volume is entitled Fundamentals of Faith, and includes translations of Maimonides’ introduction to the tenth chapter of Tractate Sanhedrin, known as Perek Heilek, from his commentary on the Mishnah, and some related matters. The newly released second volume, and the subject of the present review, is titled Conduct and Character. Both volumes are impressive looking and bear ArtScroll’s signature style of professionalism and craftsmanship that readers have come to expect.

Translation has been part of the history and reception of Maimonides’ writings since the very beginning. Most of his works were initially written in Judeo-Arabic, presumably because that made them easier to comprehend for the masses, something he explicitly acknowledges in the introductory prose passages to his Epistle to Yemen (somewhat ironically in Hebrew). But the decision to do so also limited his audience to the Arabic speaking world. Maimonides himself recognized this and expressed regret over not having composed the Sefer Ha-Mitzvot in Hebrew.[7] It would, of course, eventually receive several medieval translations (most notably by R. Moses ibn Tibbon, son of R. Shmuel, mentioned below), as well as various modern translations; the differences between them continue to generate discussion and debate.

A major drive for translating Maimonides’ works came from the Jewish communities in Luneil (and elsewhere in Provence), which had long been enamored with Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah and sought greater access to his other works. Most notably, Dalalat al-Ha’irin was translated into Hebrew by Shmuel ibn Tibbon, scion of a prestigious family of translators, as Moreh Nevukhim, or The Guide of the Perplexed. The translation of The Guide was something that Maimonides very much approved of and encouraged.[8]

While this translation would later become the standard and primary means through which Maimonides’ philosophy was known, many found its exacting translation unwieldy and difficult to use. To rectify this, and at the behest of sages in Luneil, R. Judah al-Harizi, a poet with one of the greatest commands of Hebrew in the medieval period, composed his own translation that would become very popular; it was utilized by Nahmanides, among others. But ibn Tibbon and others viciously critiqued his style and accused him of lacking real knowledge of philosophy. The debate over the proper translation of The Guide continued into modern times with R. Yosef Kafih’s 20th century translation, relying heavily on Yemenite traditions, and Michael Schwartz’s more modern edition. Translations of The Guide into English have also generated disagreement, for example, regarding Michael Friedlander’s elegant late 19th century translation that suffered from some inaccuracies, Shlomo Pines’ academic translation with its problematic Straussian undertones, and Len Goodman’s recent translation.

Even Mishneh Torah, written in mishnaic Hebrew and not Arabic, would be subjected to translation efforts. Although Maimonides strongly rejected a request to translate the work into Judeo-Arabic (in a letter to Ibn Jabar, included in ArtScroll’s Kisvei HaRambam Vol. 1, 309-324), there would be various efforts by others to make the works more accessible to those who struggled with the Hebrew. R. Tanchum Yerushalmi (1220-1291), for example, composed a dictionary of difficult words in the Mishnah and Mishneh Torah, translating them into Judeo-Arabic. Other dictionaries and commentaries, as well as partial translations of Mishneh Torah into Arabic, were also created throughout the medieval period.[9]

In more recent times, virtually all of Maimonides’ Judeo-Arabic writings have been translated into Hebrew, and many of them have been translated into English in either academic or popular editions. This brings us to the new ArtScroll volume. What makes their editions unique is what has become their popular, identifiable style of including the full text (vowelized and punctuated) on the top of the page, a line by line translation and elucidation in the middle, with font changes indicating which words are being translated and which are being added for clarity, and extensive footnotes and annotations on the bottom, including cross references to other writings, citations of other medieval and modern commentaries who have discussed similar points or argued with them, and more detailed discussions of different topics. As has become common in their recent works, the volumes include a section called “Insights,” with further in-depth discourses on various issues related to the text.

Throughout ArtScroll’s long and successful publishing history, there have been many critiques and challenges. The more serious criticisms relate to censorship of phrases or entire passages that were deemed unfit to share with the public, often with no indication that something is missing.[10] More generally, there has been disapproval as to whom ArtScroll is not willing to cite in their works, particularly those not considered part of the mainstream “yeshivish/Litvish/Hareidi” world, an approach that certainly excludes modern academic scholars, but also thinkers like R. Menachem Mendel Schneerson (the Lubavitcher Rebbe), R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik (the Rav), and R. Avraham Yitzchak Kook, to name some prominent ones. There is also the old claim that ArtScroll “dumbs down” works, thus making it easier to study without putting in the amount of work praised by traditional scholars (although it seems that one hears this objection less often nowadays).

The first ArtScroll volume of Kisvei HaRambam was met in some circles with disapproval. In Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, for example, Menachem Kellner, a scholar who has published dozens of books and articles on Maimonides, critiqued ArtScroll’s editorial decision to use a poorer edition of Mishneh Torah for their translation.[11] As Kellner notes, this is especially strange, as the editors go out of their way to explain the careful use of better editions for the other works. [12] More significantly, he charges, ArtScroll seems to craft Rambam into their own image, one that fits with their contemporary yeshivish values. After citing an idea from Michael Schwartz that Maimonides often functions as a mirror to those who look at him, Kellner writes that “even in an amusement park funhouse mirror, some connection is still discernible between the person facing the mirror and the visage reflected in it. From the perspective of most academics, the image of Maimonides found in Kisvei HaRambam is a pale reflection of the man himself.” While Kellner also has some positive things to say about the work overall, and considers it an important project (a point he reiterates in a podcast interview), his review is fairly negative.[13]

With this in mind, we can consider the content of Kisvei HaRambam: Volume 2. While the subtitle is Conduct and Character, the work can be most accurately described as a translation, elucidation, and expansion on Maimonides’ commentary on Masekhet Avot, with special focus on his introduction, known as Shemonah Perakim, or “Eight Chapters.” The text, which constitutes the bulk of the volume, is very heavily annotated and includes lengthy “Insights” at the end of each section.

The other texts included in the volume are all connected in one way or another to Shemonah Perakim or the commentary on Avot. This includes, for example, “A Letter to Ovadiah the Convert,” a selection of responsa written by Maimonides to questions (from Ovadiah the Convert himself) about the apparent contradiction between Divine foreknowledge or predetermination and free will, an issue that Maimonides discusses at length in Shemonah Perakim (and to which Maimonides refers to directly in the letter (493). Likewise, the “Letter Regarding Man’s Lifespan,” written to his prized student, R. Yosef b. Yehudah of Ceuta, about whether a man’s lifespan is fixed or dependent on his actions, is included, because it overlaps with Maimonides’ discussion of this same point in Shemonah Perakim.

Somewhat more loosely connected is the “Management of Health of Souls,” a portion of a medical work written for Al-Afdal, son of Sultan Saladin of Egypt, which is included in the work because of some (very general) overlapping of themes found in Shemonah Perakim. Even more out of place is the “Letter Regarding the Music of Yishmaelim.”[14] Maimonides mentions music in his commentary to Avot 1:16[15] as part of a longer discussion about the value of speech, and includes a lengthy digression critiquing those who assess the appropriateness of a song based on its language (i.e., Hebrew, Arabic,or Persian), rather than its content. Apropos to these comments, the aforementioned letter is translated and elucidated, wherein Maimonides explains how all music is problematic. To present a full understanding of Maimonides’ views on the role and value of music, further citations from his responsa regarding piyyutim, and his comments about music inspiring prophecy, would have been required.[16] Ultimately however, the letter is only included as an expansion on the commentary to Avot, and the general topic is thus left unexplored.[17]

The final section of the work, titled “Appendices,” includes translations of select portions of Mishneh Torah from Hilchot Dei’ot and Hilchot Teshuvah that deal with free will and character traits discussed in Shemonah Perakim. While these are relevant additions and are also annotated, there is something somewhat disjointing about pulling sections of Mishneh Torah out of context from the larger work and leaving out parts of chapters.[18]

A chapter from R. Avraham ben Ha-Rambam’s Hamaspik Le-Ovdei Hashem in translation (it was originally written in Judeo-Arabic) is also included as an appendix to this work, due to its content relevance and its citations of Shemonah Perakim, as is the introduction of the original translator of Shemonah Perakim, R. Shmuel Ibn Tibbon.[19] These appendices are less heavily annotated, and print only the translation of the text in the middle section of the page without the accompanying Hebrew words (the Hebrew text is included on the top of the page).

Finally, the volume includes a passage from Nahmanides’ commentary on the Torah, which cites and challenges Maimonides’ views in Shemonah Perakim, as well as a defense of Maimonides from Sefer Ha-Zikkaron of R. Yom Tov ben Abraham of Seville, better known as Ritva. Similarly, relevant passages from these two works were likewise included in Vol. 1. This inclusion of Nahmanides’ commentary strikes the reader as somewhat strange, considering that the passage already exists in the ArtScroll Ramban on the Torah, from which the present work borrows. By contrast, the Sefer Ha-Zikkaron, to the best of my knowledge, has never been translated, and deserves to be better known; it was thus a welcome addition. Unfortunately, no introduction or context is provided for an understanding of what this work is about, which makes it difficult to contextualize.[20]

As noted, the volume is primarily built around a translation of Shemonah Perakim. This is not the first time that it has been rendered into English; over a century ago, Joseph I. Gorfinkle published The Eight Chapters of Maimonides on Ethics (Shemonah Perakim) – A Psychological and Ethical Treatise, edited, annotated, and translated with an introduction.[21] This academic edition from 1912 includes a scholarly introduction with a discussion of manuscripts and editions, as well as a discussion of Maimonides’ thought more broadly, with many citations from earlier philosophers and scholarship. It also includes a Hebrew translation from Judeo-Arabic in the back.

In 1994, Yeshivath Beth Moshe of Scranton published a summary translation into English by R. Avraham Yaakov Finkel. In 1999, Leonard S. Kravitz and Kerry M. Olitzky wrote Shemonah Perakim – A Treatise on the Soul with a Hebrew and English text, including their own created divisions of the text and citations to other contemporary thinkers. Targum Press issued a translation in 2008 by Yaakov Feldman with extensive supplementary notes and explanations, and it features the Hebrew and English texts side by side. Though not an English translation, also noteworthy is Michael Schwartz’s translation into Hebrew in 2011, translated from Judeo-Arabic to Modern Hebrew with a lengthy introduction by Sarah Klein-Braslavy.

Not surprisingly, however, ArtScroll brings its own style and approach to the work, which differs substantially from the previous translations. The first issue that must be recognized when considering Shemonah Perakim is how much the work (particularly the earlier chapters) is indebted to, and built on, the writings of secular philosophers and their views about the nature and unity of the soul. The most significant ones are Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics and his “Treatise on the Soul,” and al-Farabi (Al Abu Nasr Muhammad) in his Aphorisms (and less frequently, Ibn Sina, known as Avicenna). Maimonides is clearly engaging with their works and responding to them.

There are certain “more traditional” commentaries on Shemonah Perakim that omit these connections, either out of ignorance or an unwillingness to engage with the source material due to their secular nature. By contrast, the more academic editions of Shemonah Perakim cite these philosophers on almost every page, noting the parallels and disagreements, demonstrating their interdependence.

ArtScroll’s Kisvei HaRambam takes somewhat of a middle path. While the footnotes are not littered with citations to the secular writers, they note in various places where Maimonides borrows an aphorism directly from Al-Farabi, among others. In Maimonides’ commentary to Avot 1:16, where he quotes Aristotle (and praises him), the authors even write that the citation is from Nicomachean Ethics (although, regrettably, a more precise location is not provided). Elsewhere, they note the difficulty in translating some of the terms, due to Arabic having adopted certain Greek terms, and therefore words had to be invented anew to approximate them (41). They point out that Aristotle himself struggled in Greek with the appropriate language at times, again acknowledging the connection. At the end of Chapter 4, when Maimonides cites an idea in the name of “the philosophers,” they explain (68, n. 122) that this is a reference to Alfarabi (the inconsistent spelling is in the original) in Aphorisms and Aristotle in Nicomachean Ethics. The willingness to cite such sources may be considered surprising, considering ArtScroll’s ideology as typically understood.

More generally, one cannot help but be struck by the large variety of citations of, and references to, medieval Jewish philosophical works, many of which are far from standard. These include, for example, Olam Katan by Joseph ibn Tzaddik (originally composed in Arabic), Sefer Ha-Emunah Ramah (The Exalted Faith) of Abraham ibn Daud, various works written by or attributed to R. Shlomo ibn Gabirol, and R. Shmuel ibn Tibbon’s philosophical glossary (appended to his revised translation of The Guide). This is in addition to references to the more well-known R. Sa’adia Gaon, R. Yehuda Ha-Levi, R. Bahya ibn Pakuda, R. Hasdai Crescas, and many more Jewish writers throughout history who engaged directly or indirectly with Maimonides’ writings.

The work also contains extensive cross-references to Maimonides’ other works, including his halakhic writings, but more substantially to The Guide, letters, medical works, including his commentary to Hippocrates, as well as his work of logic (although there remains some question as to whether Maimonides actually wrote it). One seeking further study is provided with many different paths to follow.

The volume also displays an intense desire to demonstrate how it is translating the text and which edition is being used. As noted above, Shemonah Perakim, and the commentary on Avot, was written in Judeo-Arabic, and ArtScroll relies on a recent edition by R. Ezra Korach (2009) for the Hebrew text. The footnotes, however, cite the editions/translations of both R. Yitzchak Sheilat and R. Yosef Kafih on almost every single page, while differences between their translations are noted and sometimes explained.[22] The Rambam Le-Am, an edition of the commentary published by Mossad HaRav Kook with notes from R. Mordechai Dov Rabinowitz, is also cited frequently as well. The footnotes regularly reproduce the original Judeo-Arabic word, with a citation of where the same term is used elsewhere in Maimonides’ writings, to justify the chosen translation.

Even more noteworthy is that R. Sheilat’s commentary and ideas are cited extensively. R. Sheilat is the current Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Birkhat Moshe, a yeshivat hesder, and he is also an expert on the writings of Rav Kook, not someone who most would expect ArtScroll to cite. (In the Publisher’s preface, he is identified as an eminent “Rosh Yeshiva and scholar” without further biographical details). The willingness to cite a wider array of sources does not necessarily indicate a larger ideological shift in either the publisher or the intended market, but the significance of this should not be overlooked.

In Kellner’s review of the first volume, he bemoans its failure to utilize the Yad Peshutah, a commentary on Mishneh Torah by R. Nahum Rabinowitz, who served as Rosh Yeshiva at Birkhat Moshe until his passing. In Vol. 2, the Yad Peshutah is in fact referenced several times throughout the work, also not something that one would necessarily expect. It is worth pointing out that, unlike in the previous volume, where (as pointed out by Kellner, cited above) ArtScroll failed to use better editions for Mishneh Torah, Vol. 2 uses the better accepted Frankel text, while explaining the differences between it and the older, standard edition.

The willingness to engage with Maimonides’ viewpoints, noting difficulties and questions, and even rejecting certain attempts at explaining Maimonides (even when they were proposed by Gedolim), is also significant. The thorough analysis displays a serious desire to understand the text in the context of Maimonides’ other writings and those of traditional commentaries and thinkers. Many of the “Insights,” as well, display vast erudition, and attempt to tackle some of the thornier issues in Maimonidean thinking, including the role of asceticism in Jewish thought, as well as Maimonides’ controversial view on the prohibition of earning money from teaching and learning Torah.[23]

To be sure, there is certainly what to quibble with in this work. Besides some of the issues mentioned above regarding which texts were included, some of the “Insights” are weaker than others. The one on the Maimonidean controversies, for example, lacks any historical context, and does not really provide any sense of what they were about. And there are clearly places here and there where one could question or challenge the translation decisions. Some might also point out that the edition does not properly engage with secular philosophical sources, and definitely does not cite from any of the vast academic literature written on Maimonidean thought.

These are undoubtedly valid points, but do not diminish the importance of the work. Academic editions tend to have a far more limited audience, and a translation or commentary written in such a fashion would likely be far less appealing to most readers. In his introduction to Shemonah Perakim, Maimonides himself notes that he will not necessary cite all of his sources by name, even when quoting them verbatim, because the reader may dismiss an idea from someone he does not find fitting, perhaps concerned that a harmful notion is contained therein (8-9). R. Shem Tov ibn Falaquera, a medieval philosopher and student of The Guide (cited by ArtScroll in n. 24), explains that this refers to non-Jewish philosophers whose important ideas would be dismissed and ignored if they were to be cited by name.[24] To counter many objections that some people may have of the present volume, one could reasonably argue that the authors were following Maimonides himself in their approach.

In the final analysis, ArtScroll has created an excellent edition that explains and engages with Maimonides’ work in a serious way, while still presenting it in a fashion that will be appealing to a larger audience.

[1] The Newish Jewish Encyclopedia: From Abraham to Zabar’s and Everything in Between, ed. Stephanie Butnick et al., (Artisan, 2019), 20.

[2] Although one could certainly debate if the publication of Susie Fishbein’s cookbooks constitutes one of their major accomplishments.

[3] Various works have collected statements from Maimonides’ corpus that explain and comment on biblical verses. There has also been extensive scholarship studying Maimonides’ hermeneutics and exegesis. See, for example, Mordechai Cohen, Opening the Gates of Interpretation: Maimonides’ Biblical Hermeneutics in Light of His Geonic-Andalusian Heritage and Muslim Milieu (Leiden, 2011).

[4] It would not be the first time these two were confused. See the series of sketches by the Israeli comedy group Yehudim Baim (The Jews are Coming) for a hilarious and fairly irreverent depiction of this.

[5] It should be noted that ArtScroll has been translating more and more works over the years, and it simply takes time before some get their due. When I was younger, I don’t think most would have imagined that Tosafot would ever be translated, and yet ArtScroll has in fact completed a translation of Tosafot on several tractates. A friend of mine recalled to me that his high school rebbe remarked that he will quit education when ArtScroll translated Nahmanides’ novella on the Talmud, thereby rendering his position unnecessary.

[6] See Maya Balakirsky Katz, “Maimonides in Popular Culture,” in The Golden Path Maimonides Across Eight Centuries, ed. David Sclar (Liverpool, 2003), 173-199.

[7] Iggerot Ha-Rambam, ed. Yitzchak Sheilat (Jerusalem, 1985), I:223.

[8] Although it is worth noting that Maimonides had misgivings about Ibn Tibbon’s method of translation. See James T. Robinson, “Moreh ha-nevukhim: The First Hebrew Translation of the Guide of the Perplexed,” in Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed” in Translation: A History from the Thirteenth Century to the Twentieth, eds. Josef Stern et al., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 35-54.

[9] See Simon Hopkins, “The Languages of Maimonides,” in The Trias of Maimonides / Die Trias des Maimonides Jewish, Arabic, and Ancient Culture of Knowledge / Jüdische, arabische und antike Wissenskultur, ed. Georges Tamer, (De Gruyter, 2005).

[10] See, for example, https://seforimblog.com/2016/02/the-agunah-problem-part-2-wearing/ and https://seforimblog.com/2015/06/more-about-rashbam-on-genesis-chapter-1/, Marc Shapiro, “Did ArtScroll Censor Rashi?” Response to R. Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczerg, in Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and Thought, Vol. 27, (Fall 2019), 15-25.

[11] Menachem Kellner, “Book Review: Kisvei HaRambam: Writings of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon – The Rambam,” in Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, 56:3 (2024), Summer 2024, Issue 56.3, 85-94. In the second part of Kellner’s piece (95), he reviews another work based on Maimonides, and notes how both that and the ArtScroll work list the traditional year of Maimonides’ birth as 1135, even though modern scholarship had demonstrated rather conclusively that the correct year is actually 1138. It is worth noting that in Volume 2 the birth year is stated correctly as 1138 (xiv).

[12] The editors do not indicate which edition of Mishneh Torah they are using; the reader is presumably to understand that it is the “standard edition.”

[13] This polite review (and the exchange of letters that followed) is far tamer than one featured in a 1981 Tradition article (and subsequent letters to the editor) regarding ArtScroll, then still in its infancy. The opening salvo there featured an eviscerating review of ArtScroll’s Tanakh series. To give the reader a sense, the reviewer begins by citing the rabbinic statement about the pig’s deception, as it shows off its split hooves, giving the false appearance that it is kosher. It then reads “[the ArtScroll Biblical commentary,] though far from piglike, is no less deceptive.” After critiquing the great lengths to which ArtScroll goes to proclaim its authority and accuracy, the essay ends by stating, “Not every Hebrew sign in a butcher’s window means that the meat sold is kosher.” Unsurprisingly, this review met with a strong response, some challenging the metaphors, while others disagreeing with the entire approach. Much of the exchange and review parallel the recent ones (they both bemoan, for example, ArtScroll’s selective use of commentaries and failure to cite modern scholarship).

[14] The chapter consists of two separate letters which are typically printed as such in various collections of Maimonides’ responsa, but ArtScroll, following R. Yitzchak Sheilat, whose edition ArtScroll uses (see below), considers it a single letter.

[15] Kitvei II (504) references 1:17, but it is 1:16 in ArtScroll’s edition.

[16] See Edwin Seroussi, “More on Maimonides on Music,” Zutot: Perspectives on Jewish Culture Vol 2, (2002), 126-135.

[17] One of the “Insights” has a somewhat more detailed investigation into the halakhic permissibility of music, but it does not quite engage with the letter or other sources in Maimonides’ writings.

[18] Vol.1 also includes relevant selections from Mishneh Torah. It seems pertinent to note that while there are several translations of Mishneh Torah (most of them freely available through Sefaria), a modern academic translation of Sefer Ha-Madda that includes the sections referenced here is still lacking. The Yale Mishneh Torah translation, though mostly completed by 1949, remains unfinished. The volume, including Sefer Ha-Madda and Maimonides’ introduction, has been declared as “forthcoming” for several decades now, somewhat stretching the reasonable definition of the term.

[19] One might have thought that this introduction belongs at the beginning of the work as it indeed appears in the original, but ArtScroll is not basing itself on ibn Tibbon’s translation, and they thus include it at the end.

[20] While the parallel section in Vol. 1 provides some biographical information, Vol. 2 does not even provide the full name of Ritva!

[21]The Eight Chapters of Maimonides on Ethics (Shemonah Perakim) – A Psychological and Ethical Treatise, ed. Joseph I Gofrinkle, (Columbia University Press: New York, 1912). Gorfinkle’s preface ends with the following: “It is with a feeling of trepidation that I send into the world this, my first work, fully realizing its many shortcomings. I can only hope that the kind reader will be so engrossed in these interesting Chapters of the master, Maimonides, and will find their teachings so captivating, that he will overlook the failings of the novice who presents them to him (!).”

[22] R. Sheilat’s text of Maimonides’ letters also serve as the basis for those included in the volume.

[23] Regrettably, there is no index or table of contents for the “Insights,” (although a cumulative one may appear in a future volume).

[24] It has been convincingly suggested that Maimonides is specifically referring to the “Chapter of the Statesman,” a work on ethics by the Al-Farabi. See Lawrence Kaplan “Philosophy and the divine law in Maimonides and Al-Farabi in light of Maimonides’ “Eight Chapters” and Al-Farabi’s “Chapters of the Statesman” in Jewish-Muslim Encounters. History, Philosophy and Culture (2001) 1-34.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.