Yosef Lindell

Attending the first night of Ashkenazi Selihot can be a moving experience.[1] Even though the hour is late, the shul is packed. The hazzan’s first kaddish in the nusah of the High Holidays sends a shiver up the spine and pierces the soul. Sometimes, when we sing the words of the Selihot together, I imagine our voices rising to the heavens.

Yet, it’s hard to sustain the momentum for Selihot after the first night. Attending daily means staying up late or waking up early every day until Yom Kippur. And the experience can be quite unsatisfying. The service is centered around difficult liturgical poems (piyyutim) asking God for forgiveness, and they are recited at breakneck speed. Not only does one lack time to focus on their meaning, it’s nearly impossible to vocalize every word. And it’s not just the piyyutim that are a problem. Whether one is mouthing verses from Tanakh, shouting the 13 Middot, or mumbling the litanies at the end (prayers like Aneinu), the entire service feels rushed. Erev Rosh Hashanah is the most difficult service; not only is it rushed, but it also drags due to the number of Selihot.

Don’t get me wrong. I love reciting Selihot. They meaningfully direct my thoughts toward teshuvah. The repeated chant of the 13 Middot helps me feel one with the congregation and closer to God. I appreciate the artistry of the piyyutim when I have the chance to consider it. And strangely, I even find that the frenzied rush of the service breeds an appropriate sense of desperation. Hopelessly trying to say every word, I feel helpless before God.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik writes that Selihot represent a primal stage of tefillah known as tze’akah, an “immediate and compulsive” form of prayer, which “is not bound by any requirements as to language, flow of words, sequences of premises and conclusions. [One] is free to submit his petition, no matter how informal, so long as he feels pain, and knows that only God can free him from the pain.”[2] Perhaps, then, if we speed through Selihot, comprehending little but despairing a lot, we have achieved something. If I can’t even find time to say the words to channel forgiveness—let alone understand them—what hope do I have without Divine assistance?

But this only gets one so far. The Rav said that four parts of the Selihot service are tze’akah: the 13 Middot, the verses from Tanakh, the viduy, and the litanies recited at the end.[3] The piyyutim are absent from the Rav’s list. If anything, these polished pieces of poetry are about as distant from an inchoate cry as can be. And notably, the Rav never said that one shouldn’t understand Selihot, or that it’s a good thing if one doesn’t have time to say the words.

To the contrary, this is a patently ridiculous way to daven. Kavvanah—understanding and internalization—is the cornerstone of tefillah. My teacher Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter, in his introduction to a new edition of the Selihot from Koren Publishers, collects a number of halakhic authorities that underscore that there is an “emotional inner component of Selihot recitation.” R. Schacter continues, “One cannot just read words and be done with it; one needs to be emotionally engaged with the words, to recite them as ‘words of supplication and penitence,’ deliberately, slowly, and with kavana.”[4]

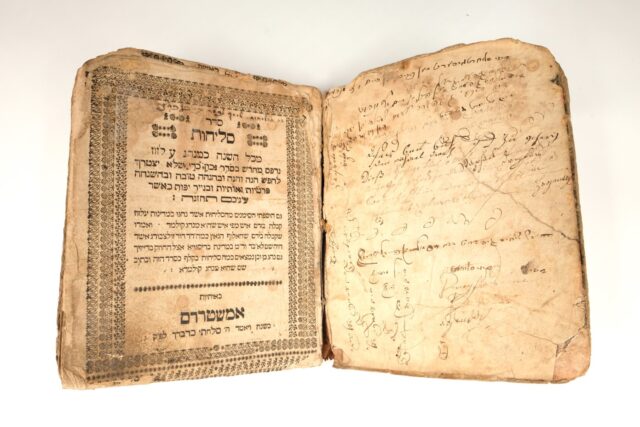

The pace at which Selihot are recited in most synagogues leaves no time for this kind of reflection, let alone for saying all the words. The piyyutim are rich repositories of meaning and history. But it is harder to contemplate what one is saying when zipping through the piyyutim, particularly when mumbling the words quietly to oneself. Before prayer books were widely available, the hazzan alone recited the piyyutim and the congregation listened, imbibing the need for repentance—especially if they didn’t understand the words—from the hazzan’s intonation and direction.[5] In fact, in some of the piyyutim, the leader speaks to the congregation.[6] The first of the Sephardi Selihot, for example, begins Ben adam mah leha nirdam, kum kera be-tahanunim – “Son of man, why are you sleeping? Arise and call out in supplication!” In chastising the congregation with these words, the hazzan seeks to awaken the worshippers from their spiritual lethargy. This is a powerful opening to the season of repentance. The way Ashkenazim recite most of the Selihot today, breathlessly and under one’s breath, can be far less impactful.

The length of the service is also a problem. On Erev Rosh Hashanah, it can easily take an hour and a half to recite all of the Selihot, which leaves even veteran worshippers exhausted and unfocused by the end. Tzom Gedaliah Selihot are also quite long, as are all the Selihot services of the Aseret Yemei Teshuvah, with the exception of Erev Yom Kippur, which is the shortest service.

Some individuals, frustrated with Ashkenazi Selihot, have turned to Sephardi services instead. Sephardim start reciting Selihot at the beginning of Elul, but the service varies less in content and duration, and the piyyutim are recited in unison. Moreover, Sephardi Selihot piyyutim are, for the most part, written in simpler Hebrew and stick to themes of teshuvah more diligently than the Ashkenazi ones, which often digress into discussing the hardships of exile, medieval Christian oppression, and acts of martyrdom.[7] In an article discussing the issues with Ashkenazi Selihot and advocating for changes, Ari Geiger, a professor at Bar Ilan University in Israel, recounts that when he attended Sephardi Selihot, he was not the only Ashkenazi present who had decided to abandon the nusah of his ancestors.

But the problems with Ashkenazi Selihot are fixable, and Tishah Be-Av leads the way. Like the Selihot, the Tishah Be-Av Kinot are long, complex, and difficult to relate to. As Chaim Saiman puts it in his article tracing the way that Tishah Be-Av has changed in the modern era, “Traditionally, people sat on the synagogue floor until midday reciting complex liturgical elegies known as kinnot in a low, dirge-like tune with little embellishment or explanation. Few had any idea what these poems meant, such that sitting uncomfortably on the floor in a darkened room did most of the work.” But, as Saiman explains, around 20 years ago, synagogues began holding alternative explanatory Kinot services where worshippers recite only a handful of Kinot and the rabbi or congregants give introductions contextualizing them historically and explaining difficult lines. These explanatory services often skip many of the Kinot. Yet, despite being in tension with the traditional approach to Tisha Be-Av, not least because of the day’s prohibition on serious Torah study, explanatory Kinot services are quite popular and have been adopted across the Orthodox spectrum.

We could make our Selihot services more like explanatory Kinot services by limiting the number of piyyutim we say each day and explaining the ones we do say. The goal of revising Selihot would be to encourage three things: (1) that Selihot are not rushed; (2) that attendees should better understand what they are saying; (3) and that the service be kept to a manageable length. The first and second goals are somewhat in tension with the third, but I’ll make a proposal.

Before the Selihot season, a congregation could choose one or two piyyutim from each day’s offerings that resonate. A piyyut could be chosen because of its message, meaning, or even its meter.[8] Each day, the congregation would recite these pre-selected Selihot slowly and with devotion, perhaps responsively, which is already how we recite the pizmon piyyut each day. Ideally, someone would give short introductory explanations to the chosen piyyutim. Since most of the Selihot are said on weekday mornings when attendees have limited time and other obligations, it will not often be practical to provide full explanations, but perhaps there could be a one minute introduction to the chosen piyyutim to help attendees focus their thoughts. Also, synagogues could offer short classes about the chosen Selihot in the evenings, on Shabbat, or even better, on the first night of Selihot. A Saturday night pre-Selihot shiur on the meaning of the piyyutim could set the tone for the entire season. (A pre-Selihot kumzitz can also help people get into the proper frame of mind, and shuls can hold both a shiur and a kumzitz.) There are also creative paths toward Selihot education. What about a podcast, for example?

Sufficient piyyutim should be removed to ensure that each service is the same length or shorter, despite going slower. Some of the Selihot are quite beloved, particularly the pizmonim, and many congregations would want to keep those. Since they are said responsively already, they tend to be better understood and appreciated. But removing many of the other Selihot piyyutim—particularly from the longer services—will provide people an opportunity to focus on what they are saying and why.

Other parts of the service could also be trimmed—it may be unnecessary, for example, to recite the section of viduy that begins Ashamnu, bagadnu three times—but portions that are mentioned in Siddur Rav Amram Gaon from the 9th century should remain as they are.[9] The recitation of the 13 Middot is the fulcrum of the service, so if some congregations feel that the Middot are not being recited a sufficient number of times because piyyutim have been eliminated, they could break up individual piyyutim into two or three parts, reciting the Middot in the middle (as is already done during Ne’ilah on Yom Kippur). Flexibility should be at a maximum, and each congregation could decide what is best for its attendees. Some congregations will say more piyyutim and some less, but one focus might be to bring Erev Rosh Hashanah to a manageable length (well under an hour, perhaps?) and to ensure that the other Selihot services could generally be finished in 20-25 minutes (or up to 30 minutes during the Aseret Yemei Teshuvah),[10] without needing to rush through the piyyutim or other portions. In subsequent years, other Selihot piyyutim could be substituted and taught, such that, over time, more of the canon would become familiar to attendees.

I’m not the first one to recognize the need for change. In Israel, there have already been efforts at Selihot reform along similar lines. Tzohar, a religious Zionist rabbinical organization, published an edition of Selihot that eliminates the piyyutim focused on exile, adopts simpler Sephardi piyyutim instead, and dramatically shortens the service.[11] Each day calls for the recitation of two Sephardi piyyutim (Ben Adam and Adon Ha-Selihot), and just one Ashkenazi one, typically the pizmon (a few more are added on Erev Rosh Hashanah).[12] Tzohar’s provocative proposal seeks to shorten Selihot, make the service more relevant and comprehensible, and enhance Jewish unity by allowing Sephardim and Ashkenazim to daven together, which is of particular concern in Israel. Yet it modifies the service drastically, and many North American Ashkenazim might not feel comfortable with it, at least at first. I am suggesting smaller modifications that may be more palatable to a wider audience. Still, Tzohar’s efforts (and those of others) speak to a need for change.

Whether one prefers the route chosen by Tzohar or the more conservative one I am proposing, there is no serious halakhic objection to modifying Selihot. Reciting piyyytim has never been halakhically mandated. For centuries, in fact, prominent poskim railed against them, including Rambam[13] and Rabbi Yaakov Emden.[14] Although the halakhic consensus today is that piyyutim may be recited, they are the newest part of the Selihot service. The 13 Middot are the core of Selihot (see Rosh Hashanah 17b), and, over time, collections of pesukim related to sin and forgiveness grew around the Middot. The poetic litanies at the end of Selihot (Aneinu and Mi She-Anah, for example) are from the period of the Geonim if not significantly older.[15] But the piyyutim themselves are not as ancient—they were composed between the 9th and 16th centuries, and each nusah calls for the recitation of different ones.[16] If anything, the pesukim sandwiched between the piyyutim and the 13 Middot, which nowadays are pushed aside in favor of the piyyutim, are more central to Selihot because of their antiquity.[17]

Some might argue that, since we do not lightly change minhagim, eliminating any of the piyyutim is inappropriate.[18] Yet, the fact of the matter is that we frequently remove piyyutim without much deliberation. On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in particular, congregations have slowly but surely eliminated piyyutim over time. One need only look at the difference between the ArtScroll mahzor—published in the 1980s—and the Koren mahzor—published 25 years later. In the Koren mahzor, more piyyutim have been relegated to the back. Moreover, already in the 19th century, Selihot were eliminated from Shaharit, Musaf, and Minhah on Yom Kippur itself. Arukh Ha-Shulhan (620:1) complained about these changes, but to no avail. Today’s mainstream mahzorim do not even include Selihot for these services. If we can eliminate Selihot on Yom Kippur itself, surely we can curtail the number of Selihot leading up to Yom Kippur.[19]

I suspect there is a broad consensus for transforming Ashkenazi Selihot in some way, even though few talk about it. Many shuls, and even more schools and yeshivot, already shorten Selihot a little, particularly on Erev Rosh Hashanah. We need to expand this project, but to do so thoughtfully. The point of shortening Selihot is not to take the easy way out, but to enhance their meaning. Many agree that Kinot reform has produced a more meaningful Tishah Be-Av. Selihot reform has attracted less attention; only a smaller group say Selihot daily to begin with, and they tend to be regular shul-goers who are often quite used to davening quickly. Also, it is harder to reform Selihot than Kinot, because Kinot are said only once a year, and many people take the day off from work, which gives them time to devote themselves to the prescribed mourning. Selihot, recited early in the morning, are always going to be one of many competing obligations. But that doesn’t make the current Selihot model ideal. Many hunger to connect to the Yamim Nora’im, and a revitalized Selihot service—with short explanations and less speed-reading—could bring more people to shul and help them engage in the demanding work of repentance. If we want to come to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur inspired by the prayerful words of our poets, perhaps we ought to recite fewer of them.[20]

[1] This article speaks to the Ashkenazi Selihot experience. As will be discussed, the Sephardi Selihot service is in less need of revision than the Ashkenazi one.

[2] Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah,” Tradition 17:2 (1978): 67-68.

[3] Ibid., 67.

[4] Jacob J. Schacter, ed., The Koren Selihot (Koren, 2022), xxi.

[5] Daniel Goldschmidt, in the introduction to his critical edition of the Selihot, writes, “One who wants to understand the piyyutim of Selihot must always remember that the sheliah tzibbur was the one who in a loud voice said the pesukim and the piyyutim in front of the congregation, and the people answered by saying only the 13 Middot. And this is [the] minhag until today in Italian, Sephardi, and Eidot Ha-Mizrah congregations.” Daniel Goldschmidt, Seder Selihot (Heb.) (Mosad Ha-Rav Kook, 1965), 9. Goldschmidt opines that nowadays, because everyone in the congregation says the Selihot together, they “fail to understand them and they do not arouse the heart” (Ibid., 10). See also Yaakov Rothschild, “Seder Ha-Selihot,” (Heb.), in Hayyim Hamiel, ed., Me-Asef Le-Inyanei Hinukh Ve-Horaah, vol. 9 (Jerusalem, 1968), 453-54.

[6] Rothschild, 476.

[7] Goldschmidt, 10; Rothschild, 453, 465.

[8] I’m partial, for example, to Selihah 85 in Minhag Lita, Arid Be-Sihi. Its short two-word phrases where the second word repeats at the beginning of the next phrase (e.g., arid be-sihi / be-sihi le-gohi / le-gohi be-hasihi) give it a breathless and broken feel, and also a Dr. Seussian rhyme. It’s unique among the Selihot, which makes it a good candidate for inclusion. Others, however, might find different piyyutim more meaningful, and some, as we will discuss, might want to focus their winnowing efforts on Selihot discussing medieval persecutions that no longer seem as relevant.

[9] R. Eliezer Melamed, in Peninei Halakha (Yamim Nora’im 2:4), details the hierarchy of the Selihot service, and readers are directed to his discussion there. He concludes, “When time is short, worshippers may skip the additional piyutim and recite just the basic order set out by R. Amram Gaon. If a congregation is selecting which piyutim to say, they should opt for those that inspire repentance.”

Seder R. Amram Gaon does not direct one to recite the viduy beginning Ashamnu, bagadnu… three times, although it includes the paragraphs beginning Ashamnu mi-kol am and Le-eineinu ashku amaleinu. See Seder R. Amram Gaon, Daniel Goldschmidt, ed. (Mossad Ha-Rav Kook, 2004), 153.

[10] See Shulhan Arukh, Orakh Hayyim 602:1: “On all the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we increase in prayers and supplications.”

[11] Avraham Gisser and Shmuel Shapira, eds., Selihot Eretz Yisrael Le-Yamim Nora’im, Nusah Rabbanei Tzohar, 4th ed. (2015).

[12] Israeli Selihot reform is driven in large part by discomfort with the piyyutim that speak to the oppression of Jews in exile, which contradicts the reality of Jewish sovereignty in Israel. See Selihot Eretz Yisrael, 7. Ari Geiger argues, “[H]ow can it be that year after year we confess before God that because of our guilt we are still in the diaspora, trampled under the feet of the kings of the other nations?” Ari Geiger, “Emet el mul Mesoret Avot” (Heb.), Makor Rishon: Musaf Shabbat (Aug. 28, 2015).

But, like it or not, Christian and other forms of anti-Judaism are a crucial part of Ashkenazi heritage. While one might choose to say fewer of the Selihot that dwell on such themes, I believe it would be a mistake to eliminate them entirely. As R. Eliezer Melamed opines in Peninei Halakha (Yamim Nora’im 2:3), “Certain passages in Seliḥot are appropriate for a period of exile, which makes it difficult for some people to identify with their content nowadays… However, if we see the Jewish people as a nation that transcends history, with each and every one of us linked to all Jews in all times and all places, we can recite even these exilic selections and identify deeply with them… How can we be so complacent as to say that the supplications of the Seliḥot are no longer appropriate, when there are still survivors among us who endured the ghettos and the concentration camps, and the world is still filled with monsters who openly proclaim that they hope to continue the work of the Nazis?”

[13] See, for example, Teshuvot Ha-Rambam 254, where Rambam writes that piyyutim “bring many things that are not relevant to prayer, and add to this a meter and tunes; tefillah leaves the category of tefillah and becomes a joke.”

[14] In his commentary on the siddur, R. Emden digresses into a diatribe against piyyutim, arguing, among other things, that “the angels too certainly do not recognize the foreign and bizarre terms that are mixed up in them.”

[15] Parts of Mi She-Anah are already found in Mishnah Ta’anit 2:4.

[16] Even today, Ashkenazim use at least three different versions of Selihot—Nusah Lita, Polin, and Anglia—and the Selihot piyyutim vary between these nusha’ot. The historical development of Selihot is recounted in Goldschmidt, 5-6, and Rothschild, 451-53.

[17] See Rothschild, 451-52.

[18] Mishnah Berurah 68:4 quotes R. Hayyim Vital about the importance of not modifying the piyyutim of the Yamim Nora’im. See also Sefer Hasidim 607 who proclaims that “there are those who die for changing the custom of the Rishonim, such as piyyutim” and tells a story of someone who died within 30 days for reciting a different piyyut than the one the congregation usually recited. But, from a halakhic perspective, it’s hard to know what to make of these kinds of anecdotes.

[19] Some congregations, albeit a minority, have returned Selihot to their rightful place on Yom Kippur, following the view of authorities such as R. Soloveitchik.

[20] I would like to thank Ted Rosenbaum for discussing the ideas in this article with me and reviewing a draft of it.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.