Gavriel Lakser

The opening chapter of Genesis has been aptly described by Michael Fishbane as theocentric in tone; that is, God is the subject and focus of the narrative.[1] From start to finish, God’s voice is the only voice heard, and it is through His commanding yet effortless speech that He brings His world into existence. As Fishbane observes, “God’s speaking and creating are one and indissoluble.”[2]

Indeed, throughout the creation enterprise, God’s creative declarations are met with full and immediate compliance; God says, “Let there be light… And there was light.”[3] (Gen. 1:3) God pronounces, “Let there be an expanse within the water… And it was so.” (v. 6–7); “And God said, ‘Let the water from underneath the sky be merged into one place…’ And it was so.” (v. 9); “And God said, ‘Let the earth sprout vegetation…’ And it was so.” (v. 11); “And God said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the sky…’ And it was so.” (v. 14–15); “And God said, ‘Let the earth sprout forth living creatures…’ And it was so.” (v. 24)[4]

Whereas the focus in Genesis 1 is squarely on the power and dominion of God, the second chapter features a palpable shift away from God as subject and towards God’s most prized creation. There, the narrative once again returns to the foundations of the world—only this time with Adam taking center stage. In contrast to the first chapter where man is created last, here, the story begins with the origins of man and follows with God’s assembling of the world around him. As Leon Kass observes, “The first story ends with man; the second begins with him.[5]”

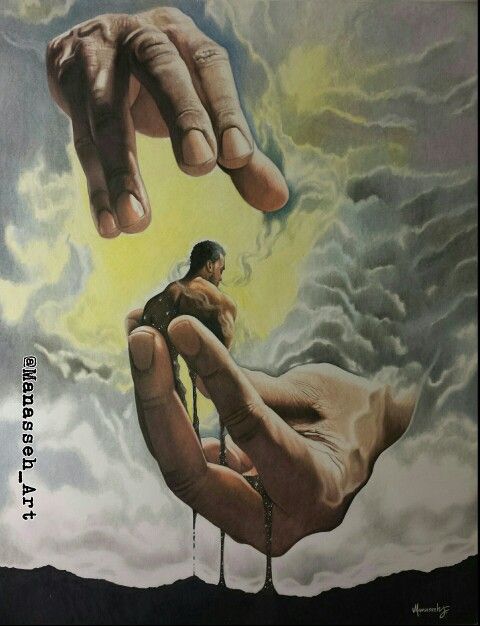

In redirecting its attention on Adam, the narrative in Genesis 2 also reveals a shift in the character of the Creator. In place of God as the transcendent, all-powerful deity who wills each of His creations into being, in chapter 2, God gets His hands dirty (as it were), forming Adam from the dust of the earth and intimately placing His mouth over the mouth of man and breathing into him the breath of life (Gen. 2:7). The God of Genesis 2 is the engaged and compassionate Creator who focuses all His attention on uplifting His most cherished creation.[6]

After bringing Adam to life, God turns His attention to the world surrounding man. Once again, there is a marked departure from the tenor of the first chapter. Although in each narrative God gives order to the world by dividing and organizing His creations, the imagery used in Genesis 2 is quite distinct from that of the first chapter. In Genesis 1, God brings form and function to His world through the rigid demarcation of boundaries; the light and darkness are sharply divided and the waters are violently pushed back to reveal the dry. In Genesis 2, however, God’s dividing of His creations is much more subtle and intricate. Here, God delicately carves out winding rivers that contour the land and which further branch out into gentle streams that nourish the lush vegetation of the landscaped garden (2:10–14). Furthermore, in place of God’s commanding speech that causes the earth to sprout forth “seed-bearing herbage,” we find His gentle cultivation of “all trees pleasing to the sight and good for food.” (2:9)

Yet God is not satisfied with providing man physical sustenance and attractive scenery alone. The earth is abound with natural resources—gold, spices, and precious stones- all of which are put in place specifically for the benefit of man (v. 12).

But all the goodness that God provides man—the breath of life, the food, and nature’s riches—is not enough to uplift Adam into a fully functional being. For Adam is lonely; he is in need of a companion.

And so, with single-minded focus, God sets out on a mission to find a helpmate for Adam. First, He forms the animals and the birds and brings them to man so as to offer him comfort[7]; “but for Adam, he did not find a suitable helpmate.” (2:20)

God then proceeds to do precisely what he does in elevating all of His creations into fully operative organisms; He separates Adam’s essential components—the male and female—into distinct bodies. However, once again taking on the flavor of the present chapter, the imagery here is of a doting parent who nurses a sickly child back to health. First, God gently induces a deep, comforting slumber upon man (v. 21) and then, without disturbing Adam’s tranquil state, carefully removes one of his ribs with which He fashions into Eve. God then tenderly sutures the flesh from where He made the incision so as to restore it back to its initial healthy state (ibid). Upon completing His forming of Eve, God presents this most perfect of gifts to Adam and awaits his response with eager anticipation.

Adam’s reaction demonstrates a vitality reminiscent of God’s other creations following division. Just as the seas and the land teem forth with life after they are divided, there is, similarly, a marked difference in man’s level of activity following God’s splitting of the male and female. What started out as a thoroughly passive being entirely dependent on his Creator for even the most rudimentary of functions,[8] the Adam we discover post-surgery finally begins to exhibit those distinctly human traits we are so familiar with. Now, for the first time, that uniquely human gift of speech is heard from Adam[9] and we see an energy in him that is so noticeably absent prior to God’s making of Eve. Adam exults at the sight of this being, so different from the animals that God initially presented to him, and so similar to himself. “This time, it is the bone of my bone, and the flesh is of my flesh!” (v. 23)[10]

Also, just as back in the opening chapter God’s other creations each receive a name and, with it, an identity after being partitioned, we find that man, too, acquires a name (“Ish” and “Isha”) that reflects a newfound identity and purpose.[11] Only now, as an exalted being, Adam takes initiative and names himself instead of relying on God’s intervention in the matter.

The story of Creation in Genesis 2 is very much man’s story. And as God’s unique love for Adam becomes clearly evident throughout the narrative, we are left to consider what it is about man that earns him God’s affection and personal attention unlike that of any of His other creations.

To answer this question we need to return to the opening chapter where on numerous occasions throughout the Creation narrative we read, “God saw that it was good.” What is this ‘good’ that God perceives in His creations?

To begin with, note that God’s recognition of the good always follows a stage in the Creation endeavor in which there is significant progress in terms of the development of life-sustaining conditions on earth.[12] The first instance comes after God’s creation of light (1:4). Both from a scientific and practical perspective, light has an essential role in the nourishment of life and wellbeing on earth. From the scientific angle, it is with light that the process of photosynthesis is initiated and, as such, light serves as the starting point to life on earth. On the practical level, light is so critical to our ability to function in any productive way. Imagine trying to forage for food in a world of complete and utter darkness. One cannot overstate the critical role that light plays in enabling us to navigate our way in the world.[13]

Next, the goodness of His creation is recognized by God following the earth’s sprouting forth vegetation, another pivotal stage in the earth’s development as a source of life (v. 12).[14] Then, with His creation of the sun, moon, and stars, God sees more goodness (v. 18). It is these heavenly bodies that give a structure and order to our lives. “Day” is the time we are active, while “night” provides our bodies time to rest and recharge. As such, each has an essential role in enabling us to function effectively. Finally, just as the division of the waters from the dry gives life to the latter, so too, the waters flourish with aquatic life following that separation. And, once again, this burgeoning of life is seen by God as good (v. 21).[15]

However, with the creation of man we find that the goodness of the world ascends to an even loftier “very good.” What is it about man that enables for the life-sustaining goodness of the world to elevate even higher?

We know that man is distinguished from the rest of the created order in being endowed with a tzelem elohim; a Godly image (1:27). According to Sforno, this divine countenance is demonstrated through man’s superior intellect which closely resembles God’s supreme intellect.[16] In other words, man is unique in his capacity as an intelligent being to contemplate and recognize the life-supporting conditions of the world he inhabits. While the world prior to Adam’s arrival is certainly good, it remains a silent goodness. With man, there comes the potential to recognize, appreciate, and respond to all the good that God has provided. It is this capacity to contemplate and reflect that marks Adam’s transition from a passive and silent creature at the onset of the narrative to the animated and passionate being that responds so enthusiastically to laying eyes on Eve for the first time. Man’s unique capacity to evaluate the world around him is further reflected in the fact that of all of God’s creations it is with him, alone, whom God speaks to instead of at.[17]

With the alternative perspective of Creation offered in Genesis 2 we discover a clear direction for the Creation enterprise as detailed in the first chapter. We find that the message of God’s unrivalled power and sovereignty in Genesis 1 is intended not to intimidate and to frighten. On the contrary, it is to provide the comfort in knowing that this thing called ‘life’ that we cherish so much is brought forth with intention by a benevolent God who ensures its stability and preservation and who compassionately endows the most exalted of His creatures with the intellectual capacity to perceive the genuine goodness of the world and its Creator.

[1] Michael Fishbane, Biblical Text and Texture (London: Oneworld, 1998), 11.

[2] Ibid, pp. 7.

[3] Translations are taken from New JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh with some modifications.

[4] Also see my essay, “Genesis 1: Creating Order with Boundaries” Times of Israel, , November 5, 2019, where I discuss the theocentric qualities to the Genesis 1 narrative.

[5] Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2006), 55.

[6] Rashi states that the name Elohim, which is used throughout the first chapter, reflects the God of judgment, while the name YHWH, which appears at the beginning of the second chapter, reflects God’s mercy (Rashi on Gen. 1:1).

[7] This follows the view of Ramban (on Gen. 2:20) who states that God presented the animals to Adam in order for him to assign names to them according to their nature, through which he would figure out which would be an appropriate match for him.

[8] See, for example, how God physically manipulates Adam in moving him in taking him and placing him in the Garden (2:15).

[9] Although the implications from Adam’s naming of the animals prior to God’s separation of the male from female are that Adam speaks, we do not hear his speech. What does he name the animals? What type of emotion does he express? The fact that the animals are not able to provide him companionship suggests that Adam speaks without much energy or enthusiasm. To be certain, he is clearly more developed and exalted than the animals even at this primitive state of development. But he is not yet the fully evolved species whose words we hear and whose enthusiasm we sense with his response upon seeing Eve for the first time.

[10] See Ramban (2:20) who reads “This time” as “This time, as opposed to the other time” in which God presents to Adam the animals and birds.

[11] The names selected, Ish and Isha (“man” and “woman”), further attest to man’s newfound state of grandeur, in contrast to the name “Adam” which reflects man’s humble origins (from adama, or ‘earth’).

[12] Jon Levenson states that the primary message of the creation narrative in Genesis 1 is of God’s “establishment of a benevolent and life-sustaining order.” (Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil (Princeton: Princeton Univeristy Press 1994), 47.)

[13] I want to distinguish, here, between the light of the first day of creation with the sun that is formed on the fourth day, which is of course what we view as the source of light from a scientific perspective. As others have argued, the Torah is not intended as a scientific account of the earth’s foundations. I would suggest that the light of Day 1 comes to demonstrate the very basic life-sustaining qualities of light, regardless of its source. The significance of the creation of the luminaries is in their function to give order to our world through their contribution to the cycle of years, months, and days which organize our lives.

[14] Note that there is no mention of the good that God perceives on the second day of creation following God’s division of the lower from upper waters because, as Rashbam states, God’s work with the waters is not complete until the third day, when the waters on low are divided from the dry. Only then does the earth (and the waters) sprout forth life (See Rashbam on 1:6).

[15] Also see my essay, “Genesis 1: The Good and the ‘Very’ Good,” Times of Israel, November 14, 2019, where I discuss the good that God sees in Creation.

[16] Sforno on 1:27.

[17] Lakser, ibid.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.