Maya Balakirsky Katz

Much of the history of Soviet Jewish culture has been informed by Cold War politics, which pinned Jewish intellectuals behind the Iron Curtain as repressed and censored and intellectuals in the Free World as liberated and unfettered. Animation tells a different story. Walt Disney Studios developed in competition to the largely Jewish live-action studio system in Hollywood, which led to popular accusations exemplified by historian Steven Kellman’s bitter observation that Disney’s films were “conspicuously Judenrein.” Soviet animation, on the other hand, attracted a disproportionate number of Jewish intellectuals and artists. While scholars Paul Reitter and David Yehuda Stern have recently argued Disney and Warner Brothers Cartoons inserted coded Jewish themes, American animators produced little Jewish subject matter. In contrast, Soviet Jewish animators made Jewish themes part and parcel of the architecture of animation and explored themes on landless minorities, the Holocaust, and national yearning.

It is interesting to learn that Soviet animators saw market forces as more limiting to artistic production than ideological censorship. The animated films that expressed Jewish subject matter were not produced underground by dissident artists but by Jewish civilian employees in a state industry. Understanding how the Soviet animation industry became a major media outlet for Soviet Jewish voices requires attention to the codes that Jewish artists established to express themselves despite the role that censorship played in Soviet culture.

Cheburashka plush toys sold in Moscow in 2012. Photograph taken by author.

Cheburashka plush toys sold in Moscow in 2012. Photograph taken by author.

One of the best examples of Soviet Jewish animation is the 1969 Soviet animated series starring a “beast of unknown origins” named Cheburashka, the Soviet equivalent of Mickey Mouse. The series embodies the personal concerns of its creative team, which was made up almost entirely of Yiddish-speaking Jews who had lost their families and homes in the genocidal campaigns during the Second World War. If scholarly literature has overlooked Cheburashka’s ethnic Jewish character and particularistic Jewish experience, filmmaker Alice Kogan and artist Tanya Levina made the connection when they appropriated the character for their post-Soviet American social organization The Cheburashka Project. In attempting to “create a portrait” of a generation of Soviet Jewish immigrants “who absorbed several worlds of influence during its formative years” Kogan and Levina envisioned Cheburashka wearing a blue yarmulke and holding a suitcase labeled “Rome” and waving an American flag.

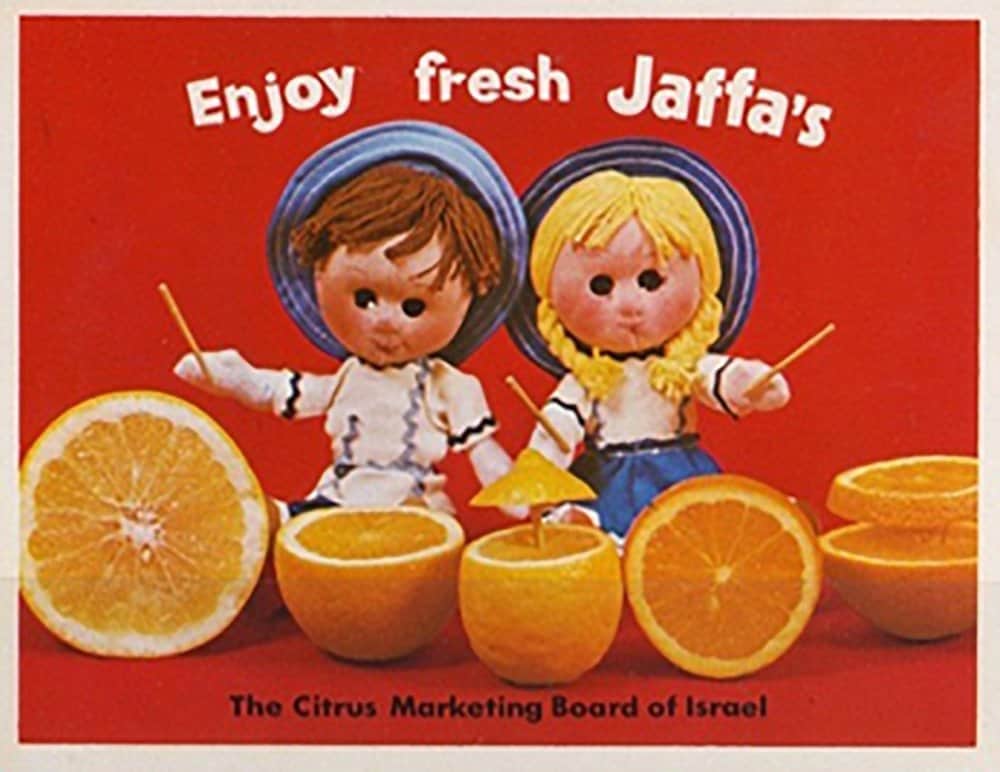

Postcard by Palphot. 1960s. Author’s collection.

Postcard by Palphot. 1960s. Author’s collection.

Cheburashka’s embodiment of the Soviet Jewish type is primarily an issue of emplacement. The first episode focuses primarily on Cheburashka’s status as “a creature of unknown origins,” a condition that leaves him unable to find a place in Soviet life. Cheburashka arrives at a greengrocer’s street stand in a wooden crate of imported oranges, which Israel studies scholar Michael Oren argues were “the ultimate symbol of Zionism—representing establishment of roots and Jewish labor.” Cheburashka’s designer Lev Shvartsman, raised in the Zionist youth culture of Minsk who changed his name to “Israel” after the 1967 War despite official hostility towards the Jewish state, would have been aware of the cultural association between oranges and Israel. Oranges were Israel’s largest and most commercially visible export after the country’s establishment in 1948, and the Soviet Union began to import Jaffa oranges in 1952. Israel’s newly established Citrus Marketing Board partnered with burgeoning Israeli industries to aggressively advertise to its international markets in an effort to tie oranges to the “Jaffa” label. They did so with commercials (including one by a former Soviet animator), posters, postcards, and dolls that featured oranges with the Jaffa label for international distribution. The memoirs of American Soviet Jewry activist Rabbi Israel Goldstein attests to the success of the advertising campaign as he reports that locals told him that “Jaffa orange juice was the most popular and widely recommended brand imported by Poland.”

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

In the Cheburashka film, the greengrocer is baffled by the appearance of this creature of unknown origins—part Russian bear and part imported tropical fruit—and takes him to the likeliest institution that could find him a place: the city zoo. The greengrocer offers the zoo guard a piece of the orange crate’s packaging instead of Cheburashka’s passport. The official declaration of “orange” for a homeless and ethnically-ambiguous character would have struck a chord for people whose internal passports listed their national identification as “Jew,” a landless minority in the Soviet scheme of multi-nationalism. The guard returns with both the homeless Cheburashka and the foreign orange document and reports that the zoological experts rejected his entry on “scientific” grounds. “No, this will not pass,” says the zoo guard in reference to the unprecedented orange passport: “He cannot be classified in the current scientific system.”

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Cheburashka’s status as a homeless outcast is most palpable in relationship to the character of Crocodile Gena who “works” at the zoo from which Cheburashka has so recently been barred. Crocodile Gena works in a park-like enclosure, complete with a pond and a tree, based on the Moscow Zoo, which replaced the use of cages in the 1920s with more picturesque enclosures such as “Goat Hill” and “Animal’s Island.” It was Crocodile Gena’s all-too-simple job in the zoo that drew the Jewish director Roman Kachanov to the project: “Can you imagine?” Kachanov repeated on numerous occasions at the studio, “a crocodile who works at the zoo as a crocodile!”

Throughout the series, there is a great deal of emphasis on the amorphous social codes that restrict Cheburashka’s desire to live and work “as himself.” In a later episode, Cheburashka expresses the hope that after he learns to read Russian and graduates from school, he will be able to work at the zoo with his friend Crocodile Gena. The wizened Crocodile Gena shakes his head: “No, Cheburashka, not for anything. It is not permitted for you to work with us.” When Cheburashka innocently asks for further explanation, Crocodile Gena cryptically responds, “Nu, why ‘why’? They’ll eat you up.”

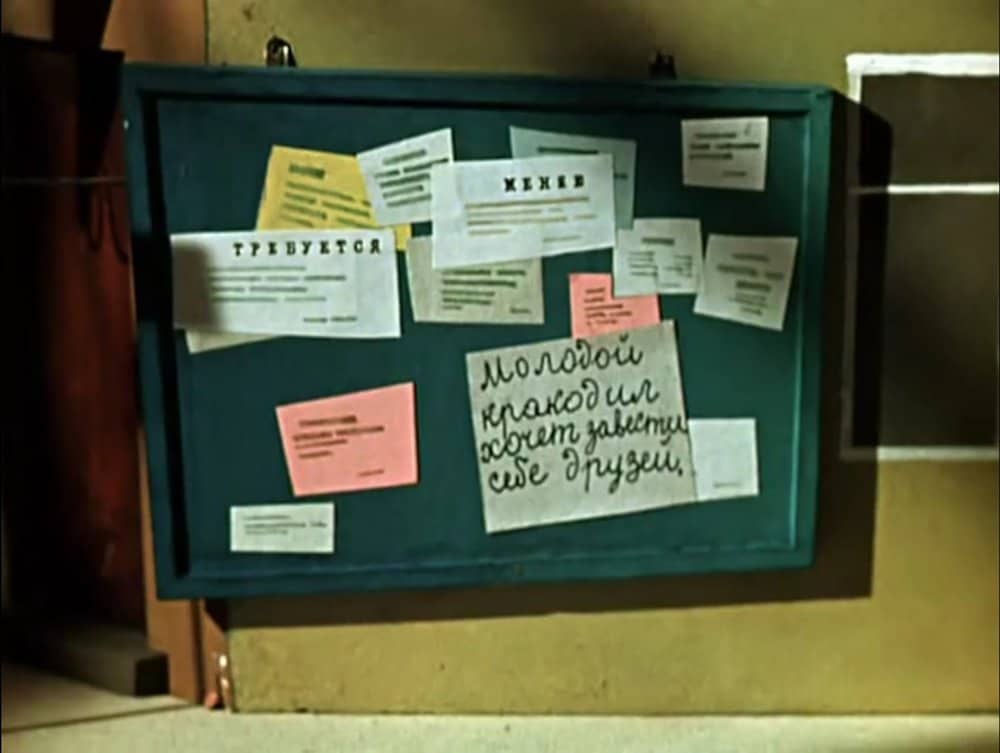

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Unlike the rootless Cheburashka, the fifty-year-old crocodile was born in the early years of the Revolution and holds the honorific “Crocodile” before his name—parallel to the title “Comrade” given to people at their places of employment. Crocodile Gena is an Old Bolshevik who walks around with a pipe dangling from his mouth in Stalin chic but at the end of the day, when Crocodile Gena is free to leave the zoo, he sits at home all alone with nothing to show for all of his compromises. Dispirited with his own lot, Crocodile Gena carefully composes an advertisement in longhand with a request for friends, which he posts all over town.

This advertisement serves to connect Crocodile Gena with Cheburashka. Rushing across town to answer the advertisement, Cheburashka meets a schoolgirl named Galya, who also saw the ad and came to Crocodile Gena’s apartment. Galya innocently asks Cheburashka: “Who are you?” Cheburashka answers in characteristic fashion, “I … I don’t know.” Galya ventures, “Are you by any chance a little bear?” Galya’s hopeful suggestion coaxes Cheburashka to identify with Russianness, at least on a symbolic level, as the bear is a widespread symbol for Russia. The drama of the moment is stretched out as Cheburashka looks hopefully up at Galya but then his ears slowly droop downward and he quietly repeats, “Maybe … I don’t know.”

The ever resourceful Crocodile Gena jumps in to help with Cheburashka’s ambiguous identity. Crocodile Gena attempts to look Cheburashka up in a thick dictionary, reading aloud: “Chai? Chemodan? Cheburaki? Cheboksary?” (Tea? Suitcase? Dumplings? [City of] Cheboksary?). Where Crocodile Gena may have found the entry for “Cheburashka” in the dictionary, he instead finds Slavic ethnic foods and local Russian place-names along with the discordant term “suitcase,” a loaded symbol that signals the theme of immigration. The exclusion of “Cheburashka” and the inclusion of “suitcase” in the Russian dictionary is fraught with meaning. Once again undefinable, Cheburashka is a scientific oddity who has no place in the zoo and no place in the Russian language. Sadly, Cheburashka makes the only reasonable conclusion: “So it means you will not be my friends.”

The series’ setting informs much of the characterization. The Moscow Zoo offered a ready-made set of historic socio-political associations for Cheburashka’s identity crisis. More than a children’s urban respite, the Moscow Zoo was a scientific organization dedicated to proving and publicly exhibiting the basic tenets of socialist society. In 1933, the zoo opened a comingling-of-species exhibition under the direction of the young biologist Vera Chaplina to demonstrate that instinctual patterns of aggression could be revamped through rigorous training. In 1936, Chaplina again garnered attention for bringing a lion cub abandoned by his mother in the Moscow Zoo to her communal apartment and raising it together with a dog. In her well-known memoir of the experience, Chaplina emphasizes the lion’s and dog’s attachment to one another and to the diverse population of people who lived in the communal apartment, especially a little schoolgirl named Galya who sided with the abandoned lion when her own grandmother launched a campaign to evict the lion from the apartment.

If the urban zoological gardens at the Moscow Zoo encompassed all the hopes of social reform in the 1930s, the same setting in the late 1960s evoked cynicism towards the synthesis of Soviet biology and social theory. The “co-mingling of the species” exhibitions became a source of well-known jokes that appeared in American Cold War-era memoirs and speeches. Director of National Security Programs at the Nixon Center, Peter Rodman once quipped:

[T]he Moscow Zoo advertised one day that it had a lion and a lamb living together in the same cage. People came from miles around to see this miraculous thing. Sure enough, there they were,a lion and a lamb, lying together side by side, apparently in perfect bliss. Someone asked the zookeeper how they had accomplished this miracle. “No problem,” he said. “Of course, we have to put a new lamb in several times a day.”

In setting Cheburashka’s rejection at the site of the historic Moscow Zoo, where animals were famously trained to live together in peace as a demonstration of the superiority of collective socialization, Kachanov and Shvartsman developed their own version of the cynical joke. Cheburashka’s official rejection from the zoo implies that despite the supposed socialist openness to genetic diversity, some “tropical” characters were simply not allowed to cross its threshold.

The Cheburashka series breathed new life into the comingling of species experiments and the Moscow Zoo setting in general, and Chaplina’s beloved stories of her experience with an abandoned lion, a faithful dog, and Galya in particular. Chaplina ended up a full-time writer and she brought her animal fables to the same studio that produced the Cheburashka series, making it likely that the project team was personally aware of Chaplina’s famous experiments on behalf of the “Friendship of the Peoples.” The first Cheburashka episode also features a schoolgirl named Galya, a lion, and a dog, all of whom find their way to Crocodile Gena’s home and immediately befriend each other despite their differences.

Outside the complex character of Cheburashka, the most “Jewish” character is the long-haired intellectual lion, Lev Chander. It is easy to detect a resemblance between the lion character and popular Soviet images of Shalom Aleichem with his facial features, swept back hairstyle, and penchant for formal dress. Director Kachanov and Shvartsman, who were both fluent in Yiddish, named the lion “Leib Chander,” a non-Slavic name with a distinctly Yiddish-sounding cadence that would translate as “Lion’s Shame” (or, the great shame). The lion’s Jewish character is reinforced when Leib Chander gives a slight bow and makes his introduction to the accompaniment of a slow and melancholic violin melody, a stylized version of Jewish composer Vladimir Shainsky’s original film score, his husky baritone voice, and his nostalgic humming at the end of the scene.

As Tobik (the good one) and Lev Chander (the great shame) walk off together into the romantically dimming light, Crocodile Gena observes in the grave voice of a philosopher: “Do you know how many people who live in our town are lonely like Tobik and Chander? And, no one sympathizes with them when they are sad.”

Unlike the non-sympathizers evoked in Crocodile Gena’s speech, Cheburashka and Galya pledge to build a community center—what they call a “House of Friends”—for the city’s alienated and misplaced folk. With some setbacks but a skirting of official building codes, the new group of friends manage to erect the community center on behalf of the lonely and downtrodden. Another bitter, historically-inflected note frames the inauguration of the community center, when Crocodile Gena announces his intention to make a “list” of everyone who has come to the House of Friends. Crocodile Gena’s desire to compile a list touches upon what the samizdat journal Khronika also called “lists” compiled by ever-present KGB agents at Jewish gathering places. An offended female giraffe that has come to the gathering reacts abrasively, “For what reason are you making a list?” Finally, at the impromptu ribbon-cutting ceremony, Cheburashka gives a short speech that has become an iconic Soviet idiom: “We were building, building, and we built. Hurrah!”

If such an overtly Jewish interpretation of the series seems far-fetched, the studio’s in-house editing body called the Artistic Council immediately flagged the film’s strange social undertones. Why, asked members of the Council, is it necessary for Crocodile Gena and ‘an unknown beast to science’ to answer the question of national belonging? Both the Artistic Council and the Ministry of Cinematography questioned Cheburashka’s uber-Pioneer activism in light of his status as a persona non-grata, a disenfranchised foreigner, and especially in light of his individualistic methods of building a community center and organizing support without official orders or any documentation. One Goskino editor disparagingly referred to Crocodile Gena and his friends as “house friends.” Veteran animator Ivan Ivanov-Vano questioned the grave seriousness of the lion character and suggests that he might wear brighter colors to appeal more to young audiences. He also questioned the “luxury” of Crocodile Gena’s apartment and then, finally, poses the central question: “Why is it a House of Friendship?”

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Cheburashka. Dir. Roman Kachanov. Ep. 1 (1969) Film still.

Ivanov-Vano astutely picked up on the ways that the film expressed a particular Jewish experience. After all, Cheburashka meets his friends and forms a small community through personal advertisements written and copied by hand in the privacy of Crocodile Gena’s home, word of mouth, apartment meetings, and grassroots organizations, which mirrored the much-criticized way that Jews organized themselves and created communities beginning in the late 1960s and throughout the 70s and 80s.

Galya meets Tobik “on the street” outside of a yellow building with a neo-classical façade that echoes the Moscow Choral Synagogue with its yellow color and neo-classical façade. The street outside the Moscow Choral synagogue was in fact a meeting place for Jews, and some scholars even cite the spontaneous demonstrations held outside the synagogue during Golda Meir’s October 1948 visit as the impetus for the first repressive policies towards Jewish national consciousness. Moscow’s Chief Rabbi Shlomo Shleifer maintained a learning program in the corner of the Choral Synagogue throughout the Khrushchev years, but those who sought to connect with organized Jewish culture were better served by informal operations on the street and in people’s homes.

Despite the apprehensions of the Artistic Council, the series was released intact. The Jewish creative team doubled semiotic systems in ways that enabled them to displace their own ethnic backgrounds on their puppets to express personally significant themes within the preexisting language of Soviet culture. Cheburashka’s coupling of a foreign tropical orange and a native brown bear and the threatening entrepreneurship of Cheburashka and his friends reflected important aspects of the lives of his creators. During a period thought to be relatively unproductive in general and repressive for Jewish artists in particular, Soviet Jewish animators managed to create some of the most expressive Jewish films in the world.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.