Leslie Ginsparg Klein

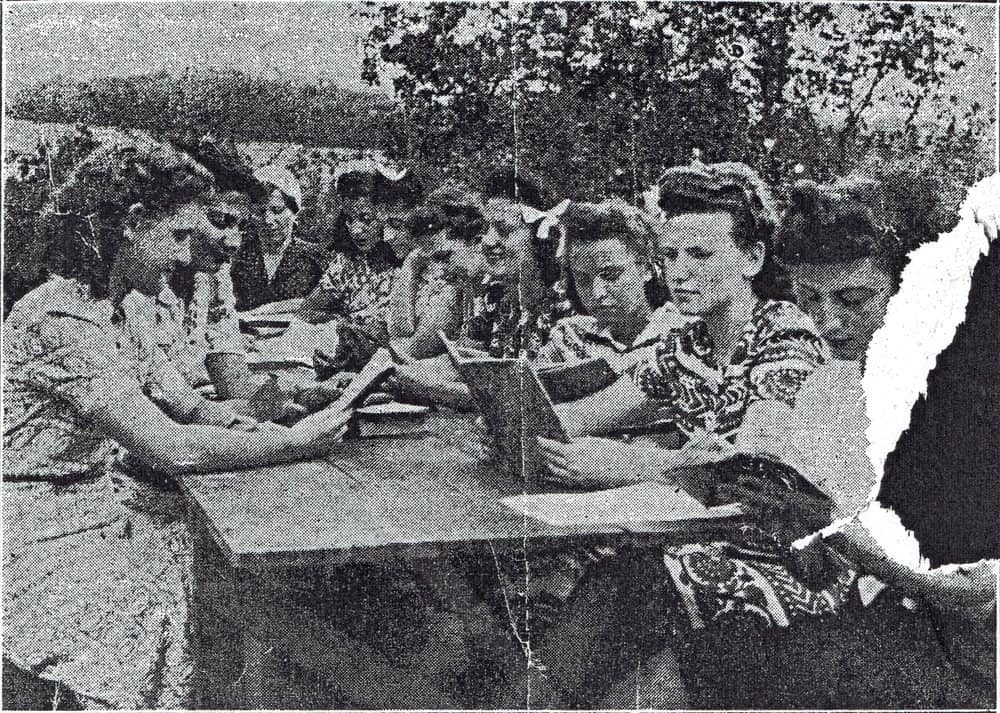

Recently, I eagerly opened up a new Feldheim biography of Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan, perhaps the greatest pioneering force of the Bais Yaakov movement in the United States. My interest was understandable: the subject occupies considerable space in my own scholarship. Flipping through the book, I was struck by a photo, snapped sometime in the 1940s. The image depicted a cluster of Bais Yaakov girls studying around a picnic table. Suddenly, I endured an unsettling, almost déjà vu feeling. I had seen this picture before, but something was off. I realized that the image staring at me had been photoshopped.

In the original photo the girls in the picture wore short sleeves. In this newer version, the students’ sleeves reached their wrists. I looked through my research and found my somewhat torn copy of the picture. The original image appeared in a school fundraising pamphlet in the early 1940s. I suddenly found myself playing a round of “Spot the Differences,” and there were many. Sleeves lengthened. Necklines raised. Knee-length hems extended an additional four or so inches. Even the married woman in the picture, wearing a full Orthodox-standard head covering, was photoshopped: the bit of hair sticking out on the sides now concealed.

Whoever doctored the image is in considerable company. This was not the first instance of an Orthodox photoshopping, an exercise no doubt meant to ensure that those pictured conform to today’s religious standards and social mores. In his recent book, historian Marc Shapiro exposed many photos (and texts) of rabbis that have been changed by their disciples and followers. For example, a bareheaded photo of the Lubavitcher Rebbe from his German university student file was manipulated; a yarmulke was drawn atop his head. This change was deemed necessary by someone within the Chabad community, even though anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of Jews in early twentieth century Germany would know that a Jewish man would not have donned a yarmulke in a university photo. The lack of yarmulke in no way reflected poorly on the Rebbe’s religiosity.

Shapiro’s work focused on rabbis, but images of women are far from immune. The photoshopping just manifests differently: for men, it’s darkened suits and hats; for women, it’s raised necklines and lowered hems.

There are many troubling notions attached to rewriting and photoshopping the past. First and foremost, it is not emes (truthful). The Torah teaches us (Exodus 23:7): “Mi-dvar sheker tirhak,” the divine directive to distance from any bit of falsehood. Photoshopping, like other forms of rewriting history, is dishonest, a corruption of the truth we are sworn to protect. The Torah does not cover up the failings of Judaism’s greatest figures. While admittedly, the Torah is not designed to be a history book, it is also not a whitewash of the Jewish past. The Torah indicates the faults of individuals—great and not great alike—to teach about our ability to grow and change. Consider Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, who averred that if the Torah presented our forefathers as perfect and “without passion, without internal struggles, their virtues would seem to us the outcome of some higher nature, hardly a merit and certainly no model that we could hope to emulate.” Rather, asserted Rabbi Hirsch, “the Torah never hides from us the faults, errors, and weaknesses of our great men … It may never be our task to whitewash the spiritual and moral heroes of our past, to appear as apologists for them. Truth is the seal of our Torah.”

Some segments within Orthodox Judaism no longer hold so tightly to these values. History has been replaced by what Rabbi Emanuel Feldman calls gadolographies, “agenda-driven stories that are devoid of content, combined with biographies that are short on objectivity and long on reverential awe, combine to create a new genre that cannot be taken seriously by anyone but the most naive and credulous.” Rabbi Feldman’s brother, Rabbi Aharon Feldman, Rosh Yeshiva of Baltimore’s Ner Israel, offered an additional criticism of this literary genre. To him, these “gedolim books” too often smack of “stereotypes” and leave out the “hard work, sweat and tears that went into making [these men] gedolim.”

In addition to being of dubious truth, these books—which rewrite history to create narratives with no challenges and characters with no faults—can be detrimental to Jewish life. Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner once wrote about how problematic he found the trend of gedolim stories that elevate great rabbis to the extent that they appear perfect, perhaps born perfect:

It is a terrible problem that when we discuss the greatness of our gedolim, we actually deal only with the end of their stories. We tell about their perfection, but we omit any mention of the inner battles which raged in their souls. The impression one gets is that they were created with their full stature … As a result [of this gap in our knowledge of gedolim], when a young man who is imbued with a [holy] spirit and with ambition experiences impediments and downfalls, he believes that he is not planted in the house of Hashem (Pahad Yitzchak: Iggerot u-Ktavim n. 128).

These were values that were once held up high by the most respected Haredi leaders. Within that same milieu, in an interesting ArtScroll volume, Rabbi Asher Bergman recounted a tale attributed to Rabbi Elazar Menachem Man Shach. The story concerns the great Rabbi Aharon Kotler, the founder of Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood. Early in its history, the Lakewood Yeshiva commissioned fundraising materials with a rendering of the school building on the receipts. On his own, the artist decided to embellish the image by adding trees to the Lakewood campus. Rabbi Kotler discarded the materials because he refused to allow his yeshiva to be founded upon any misrepresentation.

Images, then, stand for a lot. They represent beginnings, challenges, and perseverance. They tell stories, oftentimes depicting historical actors in their pursuit of noble causes. Owing to all of this, the manipulated Bais Yaakov picture is deeply problematic. Of course, Bais Yaakov in the 1940s does not perfectly resemble the image and culture of contemporary Bais Yaakov. The standards of dress across the Orthodox community differed. In those days, most married Orthodox women did not cover their hair. High school girls wore bobby socks, short sleeves, and skirts above the knees. These are the facts. To present the history of Orthodox Judaism in a refracted form, in the image of the present culture, is to miss the nuance in the lessons of history. Most of all, it ignores our capacity for change—the good kind or bad, depending on one’s perspective.

While censors may believe that they are protecting their community with their actions, they are transmitting negative messages as well. They undermine the integrity of the mesorah, a foundational belief, by knowingly rewriting the past. This censorship exercise devalues the importance of honesty and integrity in life. It trivializes the true accomplishments of historical figures.

In this particular instance, the image-doctoring undermines the great contributions of Rebbetzin Kaplan. She—like Sarah Schenirer before her—accepted students wherever they were “holding” religiously. She helped them advance from that point of departure. Rebbetzin Kaplan’s students testified that their teacher never berated them over matters of dress. Instead, she taught by example. She focused on positive messages about frumkeit and inspired girls to want to lead a frum life. In time, Rebbetzin Kaplan was successful. More and more Bais Yaakov students started to dress in line with the halakhic standards of the Yeshivish community. Today, within Bais Yaakov schools across the spectrum, covering elbows and knees are taken for granted. For the Bais Yaakov community, the photoshopped picture erase much of Rebbetzin Kaplan’s significant accomplishments and, in a way, rewrites American Orthodox history in a manner that minimizes the community’s inspiring growth in religious observance.

Yet, patient growth is an ideal that perhaps has been lost. By the late twentieth century, Bais Yaakov schools had abandoned previously “open” admissions policies. They replaced those more relaxed standards in order to restrict students who did not adhere to certain standards of behavior (including dress). This newer approach and the accompanying rewriting of the past rejects or circumscribes the idea that people are not perfect at the outset, but rather develop over time, sometimes through struggles.

Surely, editors in these predicaments are aware of the stakes, and the fraud committed by their actions. Then, why engage in these sorts of enterprises? I have heard two justifications for doctoring photos to render them more “modest.” Both reasons are flawed. First, some claim that it is not appropriate to print an immodest picture. True, in this case, the image does depict women wearing sleeves above their elbows—but there is nothing indecent about the picture. Moreover, Rebbetzin Kaplan ostensibly approved it to be included in a fundraising pamphlet. Of course, there is no reason for those offended by the students’ attire to publish the image at all. To my mind, it would be much better to exclude the picture than to photoshop the image and offer a false representation of the past.

Second, a number of apologists justify these actions on the grounds that girls will take note of the picture and become confused. They claim that the image, presented in its authentic format, might encourage immodest dress. Perhaps this is a valid concern, but it is derived from a set of values that rejects a full reckoning with history and its sources. Jewish history ought to teach students to think critically, understand nuance and change, and recognize the complexities of life, religious and cultural. Instead, by photoshopping pictures, censors miss an opportunity to present readers with an informative and inspiring message.

History, I believe, can deepen religious values. Jewish history can teach much about our past and the foundations of contemporary Orthodox life. It can be a wondrous and wonderful tool to construct a positive, healthy community. Jewish history—including our faults and foibles—can serve as a great source of inspiration. That’s why it is so important to uphold it authentically—with all of its highs, lows, and uncomfortable spots in between.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.